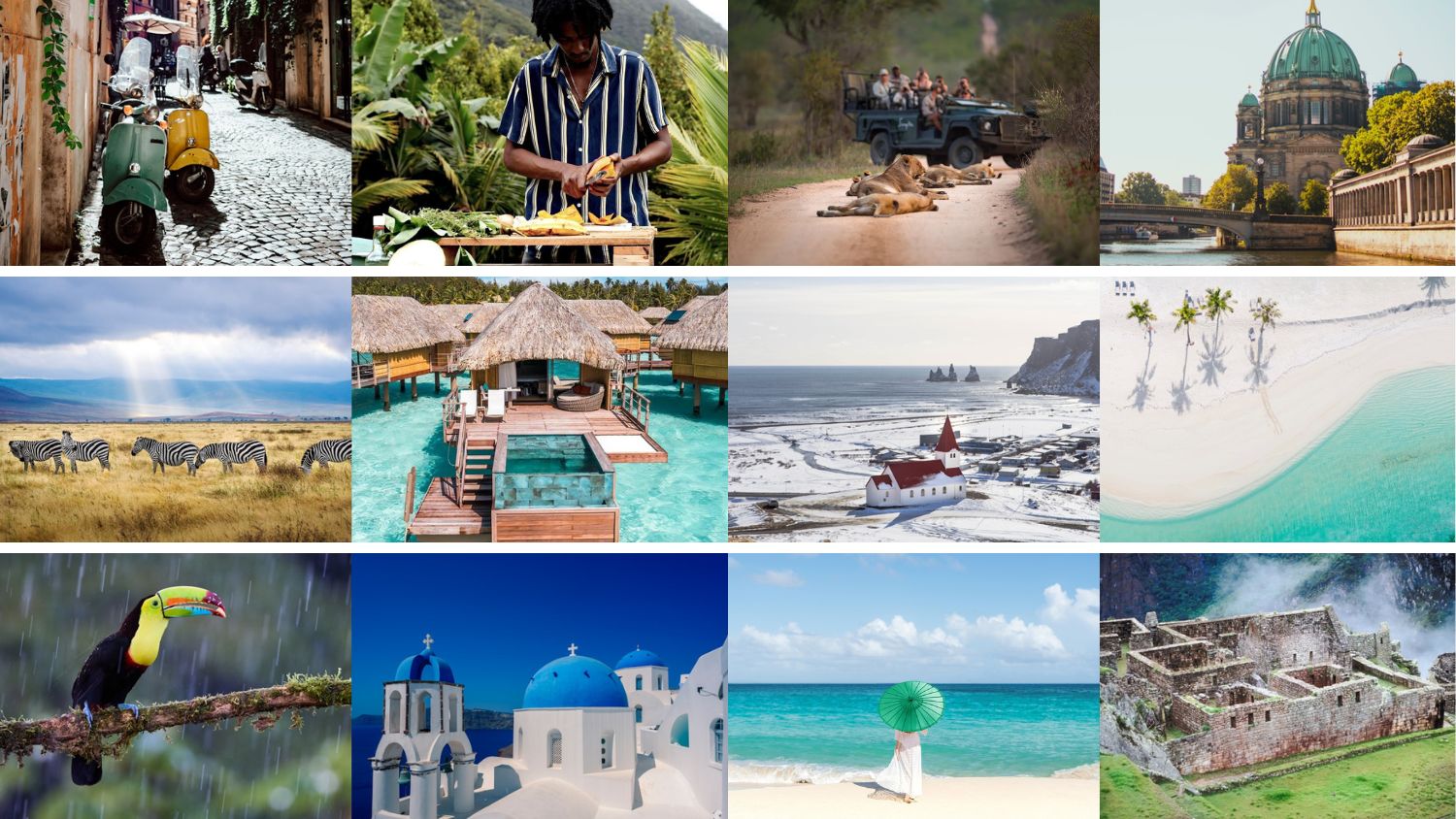

We arrive just as the beans begin to shine a bright crimson. Next week, these mountains embroidered with rows of olive-green coffee plants welcome hordes of sombrero -wearing pickers. Every year, Los Cafeteros scale these treacherous slopes – at between 1,200 and 1,800 metres above sea level (the optimum altitude for growing Arabica beans) – to supply international demand for what many claim to be the finest coffee in the world.

With wilting knees for a cracking cup of Colombian Joe, I’ve joined a 10-day, 10-person Exodus cycling tour around the central Cordillera de los Andes; a mountain range bursting through the west of Colombia. A UNESCO heritage site, Zona Cafetera (coffee growing region) enchants those looking for sublime coffee and, as I find out, surprises many with a diverse array of culinary experiences.

View this post on Instagram

ADVERTISEMENT

Without a doubt, Zona Cafetera’s main draw emanates from the Arabica bean. Colombia produces about 11.5 million bags of coffee each year and this region supplies the majority of the world. To taste the “finest cup of local coffee,” according to our guide, we cycle up to San Alberto, a farm lying in Buenavista, Quindío. Lulled by an enchanting panpipe version of The Sound of Silence, we lounge on the gravelled terrace, etched into the luxuriant mountains that shimmer shades of olive green and emerald.

San Alberto specializes in luxury coffee, seeking only the finest beans. Workers sift through batches five times, tossing aside those that don’t meet the high standards. These select few are then dried and roasted in precise-defined conditions. The significance of this escapes me and I ask the barista for a cappuccino. Tied in a maroon apron, the young woman gasps, clutches her chest and stumbles backwards. After taking a deep breath and gathering herself, she politely reminds me that “milk would only spoil the wonderful flavour, sir.” I guess she’s right. It’d be like strolling into a Russian oligarch’s reception and pouring Red Bull into the vodka. Not cool. I, therefore, resist the temptation to order a double short, low foam latte with extra cream and settle for a tinto (black coffee). I sip the chestnut brown liquid silk and allow the gentle caffeine hit to ooze down my cycle-weary limbs. Delighted, I tip my imaginary cap to the barista.

View this post on Instagram

The majority of our trip explores three provinces in the Coffee Triangle: Quindío, Risaralda and Caldas. Thanks to the diversity of our surroundings, cycling days push our senses to the brink. On dizzying descents we brush under snowboard-sized banana leaves, duck under swooping birds and inhale bitter-sweet scents from recently scythed lemon trees. We pedal alongside vast fields of sugarcane plantations, some burst from the earth like crowns of giant sunken pineapples, others lie dry and beige on the floor having been mowed down by the harvester.

In Zaragoza, a town in the province of Valle de Cauca, we pull into a row of roadside wooden shacks, their roofs spewing purple and lime-green grapes like dreadlocks. The juice provides the suitably eye-popping sweet sensation before the owner, wearing a white poncho over his shoulder, serves platters of freshly cut guava, star fruit and succulent papaya.

To fuel our 80km cycling days, which adventure travel experts Exodus labelled “challenging,” we dine at beautiful terracotta-roofed restaurants, their inner structures formed with locally-sourced guadua bamboo. We scoff traditional menú del día (menu of the day), containing fluffy white rice, grilled meat, potato and vegetable soup and a tropical juice like tomate de árbol – tree tomato. We believe this meal to be sufficient in size until we see its colossal cousin. The Bandeja Paisa has roots sewn into these rolling mountains and has kept workers, such as coffee pickers, brimming with energy for a tireless day labouring under the searing sun. Some claim this meal contains up to 2,250 calories – the same recommended daily intake for an active 31-50 year-old Canadian woman.

Bandeja Paisa consists of two types of Colombian sausage, ground beef, rice, red beans, a fried pork rind called chicharrón, an arepa, a plantain, a slice of avocado (you know, to be healthy) and a fried egg to top it all off.

When our lean mechanic Johnathan Rodriguez first orders one, our group stares open-mouthed. This mound of maroon beans, crispy pork belly, two types of sausage, egg, mincemeat, rice, a slice of avocado, a length of plantain, an arepa (cornbread) and a side of salad almost covers him from our sight. “We Colombian cyclists need the energy,” Jonathan says. Not every lunch contains such an extravagant calorie intake.

In Quindío, we explore Salento. Rows of bubble-gum-hued colonial houses line its slim streets, while dreadlocked dancers and guitarists decked in suits and trilbies entertain the swelling crowd. In the charming main square, blue and red Willys jeeps await travellers, ready to trundle them along to el Valle del Cocora.

This nearby mountainous region features an array of hiking trails, some reaching cloud forests; others, snowy peaks. In the valley, spindly wax palm trees (the tallest in the world) shoot up from the earth and puncture the low-lying clouds. Knocking woodpeckers echo through the luxuriant forest and glistening lime-green hummingbirds flutter across our brows.

View this post on Instagram

Back in Salento, a mix of international restaurants quell visitors’ appetites. Over the past decade or so, the town’s overseas population has steadily increased, bringing along Italian, Canadian and British cuisine. But for me, the most memorable dish here in Quindío’s oldest settlement lies with a Colombian favorite: the patacón. Often this green plantain, beaten flat then fried, is served as palm-sized discs with side sauces. In the open-fronted restaurants on Salento’s main square, however, huge patacones arrive bigger than a Paisa’s sombrero and with the perfect complement – hogao (a local sauce with tomato and onion).

After our brief culinary rest-bite, we head back into the glowing green coffee landscape. During the next four months (March through June) thousands of coffee pickers will strip the verdant valleys of coffee beans. And while this remarkable process has satisfied my coffee craving, it’s the local fare that has heightened my understanding of this unique landscape and, in particular, of Los Cafeteros.