A friendly, welcoming vibe is part of Amsterdam’s architectural DNA. You sense it stepping into the city’s oldest bar, the Café In ‘t Aepjen, dating from 1544. A picturesque example of a brown café, so-called for the dark wood and smoke-stained walls, the place is blessedly free of the deafeningly loud ambience of bars and restos in, say, New York. You don’t have to shout yourself hoarse to converse with pub mates

That sentiment of intimacy replicates on an architectural and city-planning scale, making Amsterdam an unusually enjoyable city for walking and biking. Think of the metaphor of the cat and the carton: If I leave an empty cardboard box lying about the living room, Gloria will snuggle inside it instead of napping out in the open on the couch.

So after several hours of sightseeing the big museums and monuments along the wide-open main boulevards, the 100-plus kilometres of narrow, intimate, tree-lined canals beckon. The three main canals, Herengracht, Prinsengracht and Keizersgracht, forming concentric water jackets around the city, were dug in the 17th century during the Dutch Golden Age when the Netherlands was briefly the wealthiest nation in the world.

PHOTO: KEVIN CLYDE BERBANO

Now, Amsterdam’s split personality reveals itself. Yes, there is the Bright Lights, Big City,but then turn a corner and the canals instantly transport you to another, more tranquil place resembling the frozen-in-medieval-time Bruges, in nearby Flanders. Water is an acoustically absorbent material, so a canal-full of it helps cut down on noise from the cobblestone pavement, enhancing the feeling of peace and quiet.

Rows of delightfully quirky gable-roofed houses line the 17th-century Canal Belt, placed on UNESCO’s World Heritage list in 2011. The window openings in the jostling facades act as private box seats to rubberneck the open-air summer concerts on the Prinsengracht Canal. Watching the neighbours watching the concert can be as entertaining as watching the musicians, who sit on a stage on a pontoon floating in front of the Hotel Pulitzer. Le tout Amsterdam turns out: stylishly coifed ladies in designer outfits and men in business suits in the exclusive ticketed seats near the stage; others watching for free from boats.

The coziness principal, if we can call it that, surely drove the jungle-gym design aspect of the famous 3D Amsterdam sign (and its Toronto knock-off), where snuggling opportunities—the loops in the lowercase “a”s, for instance—attract kids of all ages, who giggle with delight as friends snap their pictures.

Rembrandt’s Nightwatch. PHOTO BY Václav Pluhař

The Amsterdam sign fronts the Rijksmuseum, the country’s principal fine-arts museum, where

Rembrandt’s Nightwatch plays the art superstar counterpart to the Louvre’s Mona Lisa. However, while Paris’s art palace greets visitors with American architect I.M. Pei’s chilly glass pyramid erupting from an empty, wind-swept plaza, the Rijksmuseum sits on the grassy Museumplein (museum quarter). Here, the Rijksmuseum engages in urbane conversation with its arts-and-culture neighbours, the Van Gogh and Stedeljk (modern art) museums and the Concertgebouw concert hall.

Van Goh Museum. Photo: Jan Kees Steenman

The Museumplein’s stands of trees, bike paths and walkways—and the tilting, grassed-over roof of the entrance to the underground parking adjacent to the Van Gogh Museum entrance—encourage sitting, meandering and casual encounters. The 1885 building’s inner courtyards were linked to form a 24,000-square-foot skylit atrium where masses of art-loving humanity pass through the array of multi-level entrances to exhibition areas and elevator pods popping up from the floor like a ship’s funnels, or congregate at the big circular Grand Central-reminiscent information desk. The perfect vantage point to watch this hellzapoppin’ spectacle is the museum café and lounge, elevated on a platform at one end of the atrium and boasting excellent food and friendly service.

The Amsterdam sign fronts the Rijksmuseum. PHOTO BY Jennie Ramida

If you have a bucket list, even if you’re not into classical music, do visit the Concertgebouw. Yes, the resident orchestra of the same name is superb. But the star of the show is the hall’s acoustics. Critics and conductors consistently rate the 1887 building as one of the three greatest concert halls in the world (along with Vienna’s Musikvereinsaal and Boston’s Symphony Hall). The secret is the architecture: a shoe-box shape, with narrow width and high ceiling, flat floor, a raised platform with amphitheatre seating for the musicians at one end, and a shallow balcony around the three other sides. The direct sound from the stage blends with the slightly delayed reflections from the hard plaster surfaces of the walls and balcony soffits. The hall’s unusually long (2.2 seconds) reverberation time acts like the sustaining pedal on a piano. These interactions reinforce bass frequencies and give the music a full, rich, tone—the aural analogue to chocolate sauce or plush velvet.

The Royal Concertgebouw Exterior. PHOTO BY @concertgebouw

The Royal Concertgebouw Interior. ? @eduarduslee

If you’re in town for more than a day or two and want a break from the tidy downtown’hoods, take a walk on the wild side and join the hipsters riding the free public ferry that departs every 15 minutes from the Amsterdam Central Station dock to Amsterdam-Noord. You’ll glide by the brightly graffiti-ed, rusting Soviet Zulu V class submarine—a venue for private parties—located in the Maritime Quarter, the former NDSM shipyard. That submarine is a harbinger of gritty, raw, and oh-so-cool things to come. Near the ferry dock, industrial artifacts abound, such as the hulking, twisted torso of a gantry crane, with trees growing inside its trusses and weeds obscuring the black and yellow zigzags on its train-wheel bogies.

Speaking of cranes, the district’s Crane 13 morphed into the Faralda Crane Hotel, whose website advertises “spacious and high-end suites” accessible by way of a “private panorama elevator” in “the highest crane hotel in the world.” anywhere the eye alights in Amsterdam-Noord’s former port area, you’ll see graffiti. But in a profusion, variety and pristine condition that bespeak approval from city hall. Indeed, the city sponsors the most gifted graffiti creators and designates walls where budding young Jean-Michel Basquiats can legally do their thing. Not that street art here is confined to the sides of buildings. Some of the most painterly, sophisticated graphic creations adorn shipping containers or weathered concrete remains. Feeling peckish?

Crane Hotel Design Suite, Tower

Shamble over to the vibrant bohemian resto Noorderlicht Café, set within an acrylic Quonset hut, where you can catch a live samba band and then browse next door at the flea market. For one-stop shopping for a meal, free music and a relaxing urban beach ambience, the short walk to Pilek, a trendy, Texas-themed restaurant whose walls comprise stacked used shipping containers; acid-blue corrugated rusting metal walls form the primary decorating motif.

Seek and ye shall find! Just take care not to trip on bits of broken concrete and shards of steel rebar. We did say it was the wild side, after all.

AMSTERDAM ESSENTIALS

WHERE TO STAY

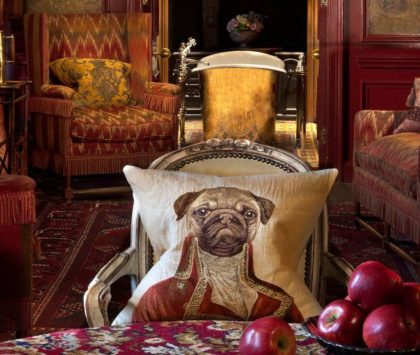

Hotel TwentySeven

The living room of the Grand Dam Square Suite, TwentySeven Hotel

The DYDELL’s ‘Tai Chi’ hand-blown luminaires from Leerdam have become a true spectacle that gives fabulous atmosphere to the hotel.

Perfectly situated at the city center, with a glimpse of the livelysquare and up close to some of the Dutch capital’s most glorious architecture, including the 17th century neo-classic Royal Palace, this hotel’s interior is just as striking, with lush, international finishings:Nepalese carpets, handmade Italian curtains and velvet wallpaper byPierre Frey France, with artwork from Amsterdam’s own Cobra Art. hoteltwentyseven.com

WHERE TO EAT

De Zilveren Spiegel

KINGFISH • Peer • Jalapeño • Komkommer • Bergamot • Dille •

Plan on a dining experience you will remember forever and reserve a table at De Zilveren Spiegel (the Silver Mirror) renowned for its delicate approach to traditional Dutch cuisine. The restaurant dates from the Dutch Golden Age, the 17th century, and all of the buildings have been kept in their original state so you can experience the ambiance of this time period. A unique evening out in breath-taking surroundings befitting the likes of Rembrandt and Vermeer. desilverenspiegel.com

MUST DO EXPERIENCE

Diamonds & Champagne Tour

The Gassan Diamonds Factory

Diamonds are forever! Book an exquisite VIP Tour at The Gassan Diamonds Factory – with champagne on hand, you’ll learn the craft of diamond polishing and view the extensive Rolex collection. gassan.com