In the eighth century, the Indian Buddhist sage Guru Rinpoché visited Bumthang in Bhutan at the invitation of the King, who had been made ill by the local deity Shelging Karpo. Transforming into the garuda, Guru Rinpoché performed the dance of the mythical bird and subdued Shelging Karpo – marking the first mask dance in Bhutan. Fast forward to today and mask dancing, based on the doctrines of Buddha and bodhisattvas, remains an integral part of Bhutanese culture. One type, the gyalong-chham, is performed exclusively by monks, and the other, boe-chham, by laypeople.

But training to become a mask dancer is intensive, agree Chogyal Rinchen and Pema Wangdi, mask dancers at the Royal Academy of Performing Arts (RAPA) in Thimphu, Bhutan’s capital. Founded in 1954 by King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck to preserve and promote Bhutan’s mask and folk dances and music, the academy has a total of 93 students, 32 of whom are mask dancers.

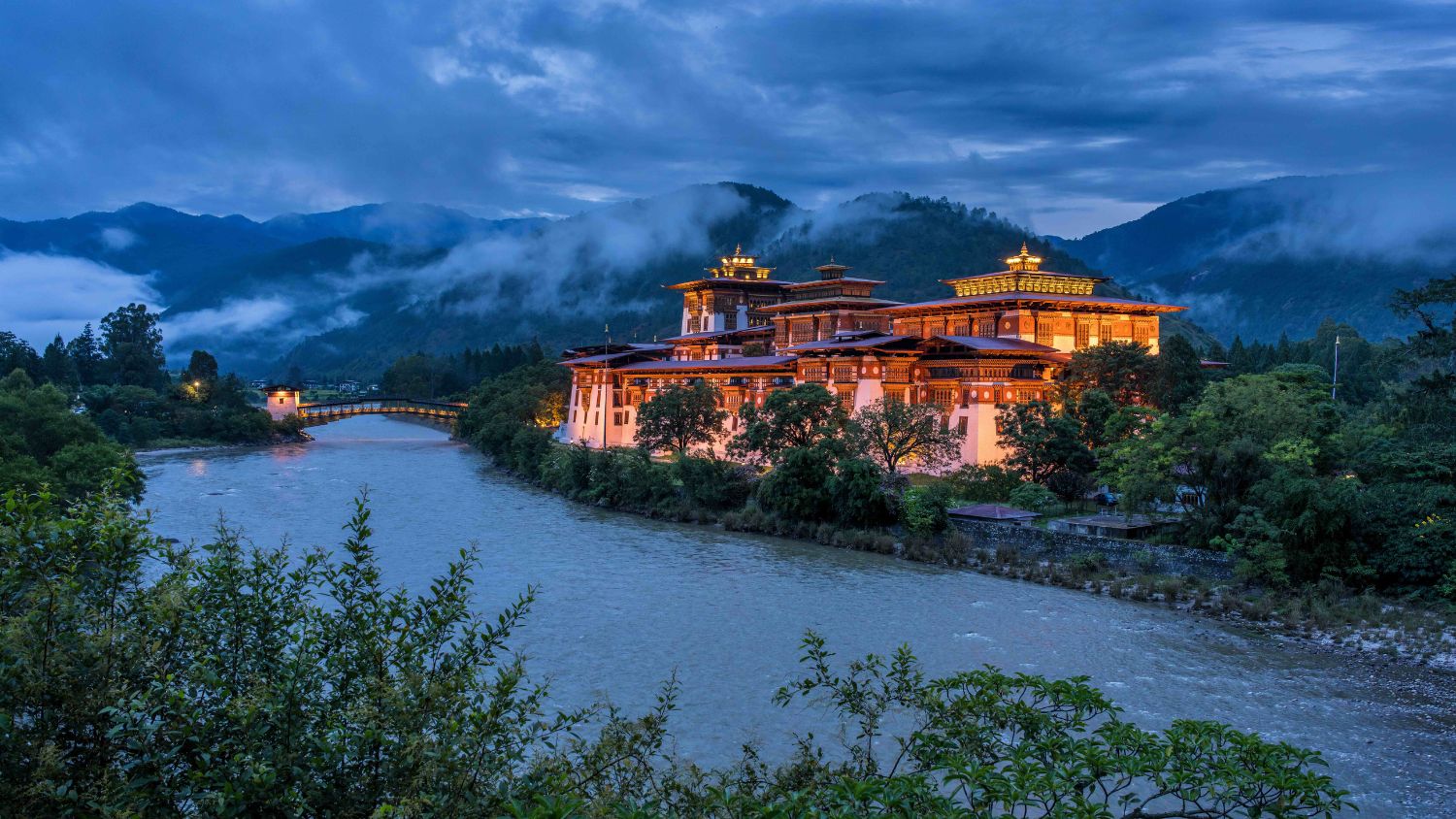

The towering Buddha Dordenma statue rises majestically above Thimphu Valley, Bhutan — a 54-meter golden symbol of peace and enlightenment housing over 125,000 smaller Buddhas within, watching serenely over the land from the lush Kuenselphodrang hills. Photo: Amp Sripimanwat

Being accepted is no mean feat: auditions are held based on artist shortages and last an entire week, with female and male contestants having to demonstrate an aptitude in all three disciplines (mask dancing, folk dancing and music), explains Phub Wangdi, the Vice Principal of RAPA. They also need a grade 12 education, to have no criminal convictions, and to be in good physical and mental health.

If they’re accepted, they train for four years – eight hours a day, five days a week – learning from three teachers specializing in mask dancing. Chogyal, who is 32 and from Khengkhar village in the district of Mongar, recalls one teacher saying he needed to lift his legs to knee height, something quite difficult. Students must pass multiple choreography exams before becoming professionals and performing at festivals; however, mask dancing is about more than earning a livelihood. “It’s very sacred in our culture,” says Pema. “We believe that mask dancers have an easier way towards enlightenment.”

A group of male dancers get ready for a traditional item during Thimphu Tshechu (festival). Photo by Pema Gyamtsho

Pema is 29, a former chef and from the village of Khoma, the famous home of the kishuthara, a type of kira (Bhutan’s national dress) woven from intricately patterned silk. Even more vibrant are mask dancing costumes, crafted from colourful purloin cloths. When preparing for a performance, the main challenge is dancing barefoot on sunny days, say Chogyal and Pema. Sometimes, they stop the practice to sprinkle water on the ground.

Another is the mask’s weight – nearly one kilogram – making turning gracefully harder than it looks. Dancers also need to learn to bow with their hips, instead of the traditional way using their necks, and give each other enough space, ensuring their costume threads don’t get tangled in the masks.

Audiences dress their best too, with programmes in Thimphu attracting up to 8,000 spectators. “People are so bright and colourful they’re like little flowers in a garden,” says Chogyal. On average, professional dancers attend 20 programs per year, from festivals to more intimate events for royals, state guests and other special foreign visitors. Performances take place in Thimphu, and travellers are welcome to attend the festivals (Bhutan has more than 150 each year, and the only cost is a small monument fee wherever needed). Dancers also travel to teach in other districts such as Wangduephodrang, Gasa, Trashigang and Gelephu for local festivals, and the academy’s exchange program gives them the chance to share their vibrant culture outside of Bhutan too, including in Bangladesh, Dubai, Hawaii and Switzerland.

Programs in Bhutan to look out for include Haa Spring Festival in April, set amongst alpine flowers in the Haa Valley, and National Day on 17 December, commemorating the coronation of the first king of modern Bhutan, and celebrated across the country.

A vibrant moment from Thimphu Tshechu — Bhutan’s grand annual festival honoring Guru Rinpoche. Held each autumn in the capital, it’s a dazzling three-day celebration of devotion, dance, and color. Photo: Nithil Dennis

Chogyal and Pema are most excited for Thimphu Tshechu, a festival honouring Guru Rinpoché, in early October (these dates are based on the Gregorian calendar, but travellers should keep in mind Bhutan uses the lunar calendar for religious festivals like this one). The days are packed, with dancers arriving at the venue at 7am, and not returning home until around 6pm. “Sometimes, we’re so tired, we fall asleep without eating dinner,” laughs Chogyal.

On the third day of the festival, many people gather to see the Raksha Mangcham, a popular dance that shows what happens after you die and before you’re reborn, and to receive blessings. In the elaborate performance, a kind spirit and fearsome prosecutor count the good and bad karma of a recently deceased soul, deciding if they’re going to hell or heaven. “It’s a reminder to be more compassionate, and that everything is impermanent,” says Chogyal.

“Dancers are taught to think of themselves as the mask they are wearing, transforming their mind, body and speech,” explains RAPA’s VP Phub Wangdi. As soon as someone puts on the red, smiling mask of Atsara – a jester who carries a phallus – for example, he becomes the Atsara. “Even if they’re shy, they crack jokes and do funny things, making people laugh,” says Chogyal. “If we’re wearing a mask of a peaceful deity, we imagine that we are them, and we’re dancing amongst the gods and goddesses in heaven.”

“You have to be very mindful and present,” adds Pema, who prays those watching him dance might find the path to enlightenment. “One of the purposes of visiting the festivals is to accumulate good karma.”

Dancing is a devotion. “When I dance, the feeling is deep and different,” says Chogyal. “I think, where have I reached? What place is this?” For those lucky enough to see mask dancing in Bhutan, the feeling is similar.

*With special thanks to Kezang Choden, Marketing Public Relations Officer at Bhutan’s Department of Tourism, for helping to translate.